Who was the real Joan Aiken, and how far did she go in writing about her own life?

“This story is just too hard to swallow!” was the editor’s note on an early story she submitted. Remembering this years later, she said: “He was talking about the only story I ever wrote, flat, from real life, and it taught me a useful lesson about the risks of using unvarnished experience.”

Most writers have learned the wisdom of a little concealment in their work – no one wants to be sued, (and in her early writing days she had a few warnings about this possibility – see below) or to be at the mercy of endless angry letters about the misrepresentation of a reader’s well loved home town or village, or heaven forbid, incur outrage even closer to home with dangerous disclosures familiar to their own relations…

(signature illegible I hope!)

So does Joan Aiken’s most mysterious possibly autobiographical 1980’s novel, Foul Matter, tread a fine line?

It was for instance accepted literary practice in Milton’s day to give all your characters names from Greek mythology, not necessarily to conceal their identities, but to set them in a more idyllic or ‘pastoral’ landscape. A clue to Joan Aiken’s intentions in this possibly autobiographical novel lies in the chapter headings she has chosen to take from Milton’s famous Pastoral Elegy, Lycidas and whose muses she invokes at the opening of her book: ‘the sisters of the sacred well.’ Milton’s poem was written as a song of mourning for his friend and fellow student who had drowned when his ship sank off the English coast – as does Dan, the heroine’s husband in this novel. Joan’s first husband Ron took her out to sea when they were moving house from Kent to Sussex and sank the boat and all their possessions just off Whitstable, but happily that time nobody drowned – in fact the family were rescued by some passing sea scouts, but who would believe that?

Clytie, or Aulis or Tuesday, the heroine of Foul Matter, has many different names, and does speak in the first person, but is this her author’s voice? She has such an astonishing amount of unfortunate history and such numbers of lovers that reviewers of the novel said it had to be a lurid Gothic fantasy – surely even in the 1980’s people didn’t live like this? When Tuesday first appeared in an earlier Aiken thriller (The Ribs of Death – another quotation from Milton) she was introduced as the author of a spoof (and sexy!) shocker while still in in her teens:

“You wrote that novel, didn’t you—Mayhem in Miniature? Aren’t you Aulis Jones?”

Certainly this can’t have been autobiographical, as when no publisher will touch Tuesday’s second literary attempt, she is forced to become a caterer instead, and although Joan Aiken was an excellent and inventive cook, and descriptions of recipes in Foul Matter give plenty of evidence for that, in real life she is better known as the author of over a hundred works of fiction.

Conrad Aiken, Joan’s father, wrote a fictionalised autobiography in which the characters all had other names, even his wives and children, although in the tradition of the Roman à Clef an index of real names was provided in later editions. He also wrote an elegy, a poem called Another Lycidas, for an old friend who died. This tradition of using different literary forms and references was in the reading and writing blood of the family, so Joan Aiken had plenty of background both real and fictional to draw on; and her own family history, like that described in this novel, was full of extraordinary deaths.

So how to consider it? We are given another clue in the novel’s title, Foul Matter and in the heroine’s conversation with her publisher about a completed, and nicely ironically titled recipe book:

‘“By the way,” he said, “do you want the foul matter from Unconsidered Trifles?”

Foul matter is a publishers’ term for corrected copy that has been dealt with and is no longer in use: worked-over typescript and proofs.

“Throw out the old copy,” I told George. “I don’t want it.”

Foul matter. Who needs it? You might as well keep all your old appointment books, mail order catalogues, nail clippings, laddered tights, broken eggshells, bits of lemon peel. Some people do, of course, and just as well, or history would never get put together. But I’m not one of those. History will have to get along without my help. Life, memory, is enough foul matter for me.’

True or false? When I came to clear out her attic (‘Don’t call it the attic, it’s my study!’) I was astonished to see how much she had kept – school reports, ration books, letters, letters, letters… all grist to the mill of her imagination, or background for other, fictional characters? How much of Joan Aiken’s life did get filed away in her writing? There are plenty of descriptions of houses and towns she knew and loved, but which ones are they really, were any of them her own? Is Foul Matter set in Rye or Lewes, where she did live, or perhaps both? It has the castle mound of one and the salt marsh of the other:

‘Dear little ancient house. Watch Cottage. I always turn to look back at it with love. White, compact, weatherboarded, tiny, it stands in dignity below the brambly Castle Mound, at the head of a short, steep, cobbled cul-de-sac, Watch Hill, which leads down into Bastion Street… On down the steep hill; the town of Affton Wells displayed below my feet like a backdrop in flint, brick, and tiled gables. Tudor at the core, seventeenth and eighteenth century on the perimeter. Grey saltmarsh beyond, receding to the English Channel.’

In her father Conrad’s version, Rye, his adopted English home town where Joan was born, became Saltinge, a picturesque little East Sussex town with weatherboarded houses and marsh views, so reminiscent of New England where he had grown up, and which he yearned for constantly when back in America.

Perhaps Joan Aiken’s novel, written in her sixties at the height of her career, was an attempt to throw out the old memories, junk the lingering Foul Matter, move on to a new era, or to pay tribute to friends loved and lost; to store their memory forever in a fictional world where she could go back and visit whenever she wanted. Who is to say what is truth and what is fiction?

All I know is that whenever I want to spend some time with her, this is the Joan Aiken novel I turn to.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

P.S. Looking back through some of those letters I found mention of an invitation to a private film-showing where she met: “a splendid British film tycoon called Sir J. A. who was just off to his château on the Loire, and very frosty at first, but finally thawed enough to buy me a whisky…” The model for Foul Matter’s Sir Bert Wilder perhaps?

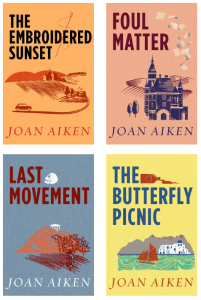

Foul Matter is now available as a new paperback

All Joan Aiken’s modern novels now available as EBooks

Find new editions of Orion early thrillers here

and Modern novels from Bello Macmillan here

Hmm, I already have The Cockatrice Boys, Jane Fairfax and The Haunting of Lamb House waiting patiently, dare I add another one to the queue? Umm…

LikeLike

You know you want to…

And of course I always look forward to hearing your thoughts!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating! I love the heroine’s description of foul matter especially. I have to admit, though, that I’m more of a historian myself, by both inclination and training. (And the historian in me hopes that all those school reports and letters were saved!)

LikeLiked by 1 person

The website is testament to that..! eg. School Reports: https://www.joanaiken.com/timeline/

I like to think of it as a virtual museum, sharing a bit of background and period detail.

But who she really was shone out through her writing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

And what an excellent virtual museum it is!

LikeLiked by 2 people